Snitching on Phones That Snitch On You

Purism

Latest posts by Purism (see all)

- A Quarter Century After Cyberselfish, Big Tech Proves Borsook Right - December 20, 2025

- PureOS Crimson Development Report: November 2025 - December 15, 2025

- Purism Liberty Phone Exists vs. Delayed T1 Phone - December 10, 2025

Our phones are our most personal computers, and the most vulnerable to privacy abuses. They carry personal files and photos, our contact list, and our email and private chat messages. They also are typically always left on and always connected to the Internet either over a WiFi or cellular network. Phones also contain more sensors and cameras than your average computer so they can not only collect and share your location, but the GPS along with the other sensors such as the gyroscope, light sensor, compass and accelerometer can reveal a lot more information about a person than you might suspect (which is why we designed the Librem 5 with a “lockdown mode” so you can turn all of that off).

One of the problems with the security measures implemented in Android and iOS is that they restrict the user as much, if not more, than they restrict an attacker. Ultimately Google and Apple control what your phone can and can’t do, not you. While these security measures are marketed as making your phone a strong castle you live inside, that’s only true if you hold the keys. As I mentioned in my article Your Phone is Your Castle:

If you live inside a strong, secure fortification where someone else writes the rules, decides who can enter, can force anyone to leave, decides what things you’re allowed to have, and can take things away if they decide it’s contraband, are you living in a castle or a prison? There is a reason that bypassing phone security so you can install your own software is called jailbreaking.

You not only don’t have much say over what Google or Apple do on your phone, but also these security measures mean you can’t see what the phone is doing behind the scenes. While you might suspect your phone is snitching on you to Google or Apple, without breaking out of that jail it’s hard to know for sure.

Your Phone Snitches On You

It turns out if you did break out of jail and monitored your phone, you’d discover your phone is snitching on you, constantly. A research paper just published by Douglas J. Leith at Trinity College in Dublin Ireland says it all in the abstract (emphasis mine):

We investigate what data iOS on an iPhone shares with Apple and what data Google Android on a Pixel phone shares with Google. We find that even when minimally configured and the handset is idle both iOS and Google Android share data with Apple/Google on average every 4.5 mins. The phone IMEI, hardware serial number, SIM serial number and IMSI, handset phone number etc. are shared with Apple and Google. Both iOS and Google Android transmit telemetry, despite the user explicitly opting out of this. When a SIM is inserted both iOS and Google Android send details to Apple/Google. iOS sends the MAC addresses of nearby devices, e.g. other handsets and the home gateway, to Apple together with their GPS location. Users have no opt out from this and currently there are few, if any, realistic options for preventing this data sharing.

I should note that both Google and Apple dispute some of the findings and methodology in this paper which you can read in reporting by Ars Technica. Yet I should note they don’t seem to dispute that they do this (because they claim it’s essential for the OS to function), they only quibble over how much they do it, how much bandwidth is used, and how much the user can opt out of this telemetry. Even more telling is Google’s defense in the article, which perfectly summarizes how they view the world:

The company [Google] also contended that data collection is a core function of any Internet-connected device.

Just to underscore the point, we aren’t talking about the massive privacy issues with apps on your phone that snitch on you to app vendors, instead this study focused just on what the OS itself does, often in the background while idle, or while doing simple things like inserting a SIM card or looking at settings. Also, the data that is being shared uniquely identifies you (including your IMSI and phone number, IP and location) and your hardware (IMEI, hardware serial number, SIM serial number).

How to Snitch On Your Phone

The Librem 5 runs PureOS and not Android nor iOS, and Purism is a Social Purpose Company that puts protecting customer privacy in our corporate charter. We treat data like uranium, not gold, and don’t collect any telemetry by default on the Librem 5 phone just like we don’t on our other computers. The only connection a Librem 5 makes to Purism servers is to check for software updates and you can change that by pointing to one of our mirrors or you can disable the automatic checks entirely. In that communication all we get is a web log of an IP address and any software you may have downloaded, the same information you share when you visit any other website. We do not capture unique identifying data (like IMEI or other hardware serial numbers) that links that traffic to you and your phone.

In general the Librem 5 only talks to the Internet when you start an application that needs it. All of the applications we install by default respect your privacy and applications within PureOS do as well. Because everything in PureOS is free software, if an application wanted to violate your privacy they’d have to do it out in the open in the source code, and if someone didn’t like it, they could fork the code and publish a version without that telemetry.

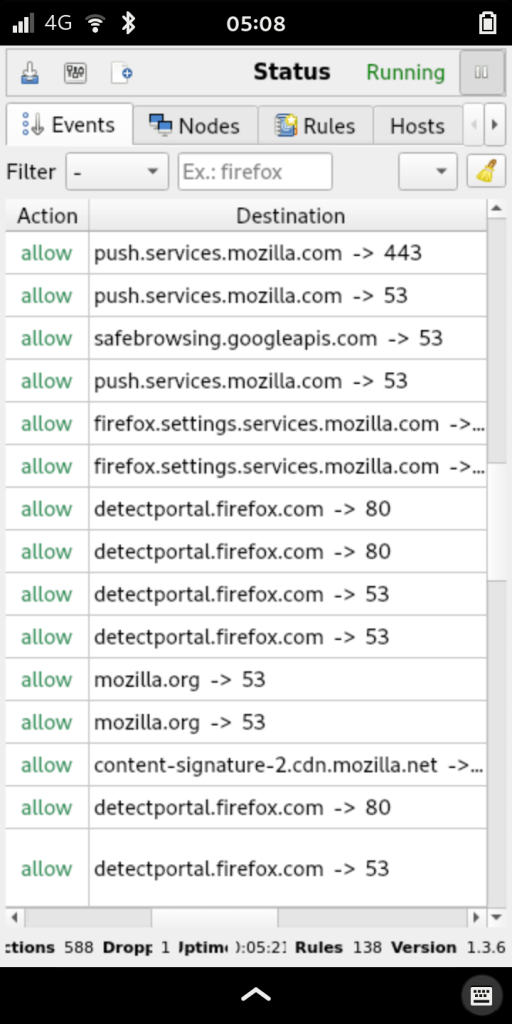

That said, there are some applications you can install like Firefox that do collect telemetry by default. While you could audit the source code to look for anything sketchy, it would be even better if you could just monitor all of the outgoing network connections your applications make and block any you don’t like. While we think you should trust us when we say Purism doesn’t spy on you, we also think you should be able to verify our claims and protect yourself. This is where a tool like OpenSnitch comes in.

OpenSnitch

OpenSnitch is inspired by a similar program on MacOS called Little Snitch and it acts as a firewall for a desktop user. Unlike traditional firewall tools that were designed for servers and mostly concerned with incoming connections, OpenSnitch works on the principle that the larger threat on desktops isn’t incoming connections (since desktops rarely have open ports anyway) but outgoing connections. On a desktop an attacker trying to connect to a vulnerable network service is a relatively low threat. A much larger threat is an application that gets compromised (or added sketchy features that haven’t been caught in a code audit) that starts making unauthorized connections out to the attacker’s servers.

While OpenSnitch isn’t yet packaged for PureOS, I’ve been evaluating it on my Librem 5 for a few weeks now. Even though I’m running the regular desktop version of OpenSnitch, it works surprisingly well on the Librem 5 and while the interface is complicated with lots of tabs and tables, it actually fits well on the screen already.

OpenSnitch monitors all new outgoing network connections and alerts you when something new shows up it doesn’t already have a rule for. The alert shows which application is making the connection, where it is connecting, and on which port. You can then choose to allow or deny the connection, and whether to apply this rule forever, until the next reboot, or for a number of minutes. There is also a 15 second countdown timer that will deny the connection after it times out. The idea here is to protect your computer from unauthorized outbound connections when the computer is unattended.

You can also click the + button and fine-tune the rule. This can be handy if you want to allow a program to access DNS regardless of what it’s looking up, so you can just select port 53. You can even restrict a rule so it only applies to a particular user on the system.

OpenSnitch is a really powerful tool but software like this requires a lot of time spent training the firewall, and can sometimes cause odd app errors until you realize the firewall is just doing it’s job. It would definitely benefit from a set of “known good” baseline rules you could apply so you only get prompted for the real outliers. Because of this I don’t know that it’s something the average user would want to install by default, but it’s definitely something useful for people facing more extreme threats.

This would also be a great tool for an IT organization to deploy throughout a fleet of computers along with custom rules that factor in their known good services. It would add an additional layer of protection that would be relatively seamless for their employees.

A Phone That’s On Your Side

A phone that snitches on you and sends a trove of personally-identifying data back to the vendor every few minutes, even if it’s idle, is not on your side. A phone that’s on your side helps you snitch on them. A phone that’s on your side honors your opt-out requests and ideally requires you to opt-in to anything that risks your privacy. A phone that’s on your side doesn’t collect your data, it protects it.

Discover the Librem 5

Purism believes building the Librem 5 is just one step on the road to launching a digital rights movement, where we—the-people stand up for our digital rights, where we place the control of your data and your family’s data back where it belongs: in your own hands.

Recent Posts

Related Content

- A Quarter Century After Cyberselfish, Big Tech Proves Borsook Right

- PureOS Crimson Development Report: November 2025

- PureOS Crimson Development Report: October 2025

- Landfall: A Case Study in Commercial Spyware

- Librem PQC Encryptor: Future‑Proofing Against Both SS7 and Quantum