Librem 5 general development report — February 13, 2018

Purism

Latest posts by Purism (see all)

- A Quarter Century After Cyberselfish, Big Tech Proves Borsook Right - December 20, 2025

- PureOS Crimson Development Report: November 2025 - December 15, 2025

- Purism Liberty Phone Exists vs. Delayed T1 Phone - December 10, 2025

Back from FOSDEM

Being at FOSDEM 2018 was a blast! We received a lot of great feedback about what we have accomplished and what we aim to achieve. These sorts of constructive critiques from our community are how we grow and thrive so thank you so much for this! It helps us to focus our development. Moreover, I was very impressed by the appreciation that we received from the free software community. I know that relationships between companies, even Social Purpose Corporations—like Purism, and the free software communities are a delicate balance. You need to find a good balance between being transparent, open, and free on one side but also having revenue to sustain the development on the other side. The positive feedback we received at FOSDEM and the appreciation that was expressed for our projects was great to hear.

We are working really hard on making ethical products, based on free/libre and open source software a reality. This is not “just a job” for anybody on the Purism staff, we all love what we do and deeply believe in the good cause we are working so hard to achieve. Your appreciation and feedback is the fuel that drives us to work on it even harder. Thank you so much!

Software Work

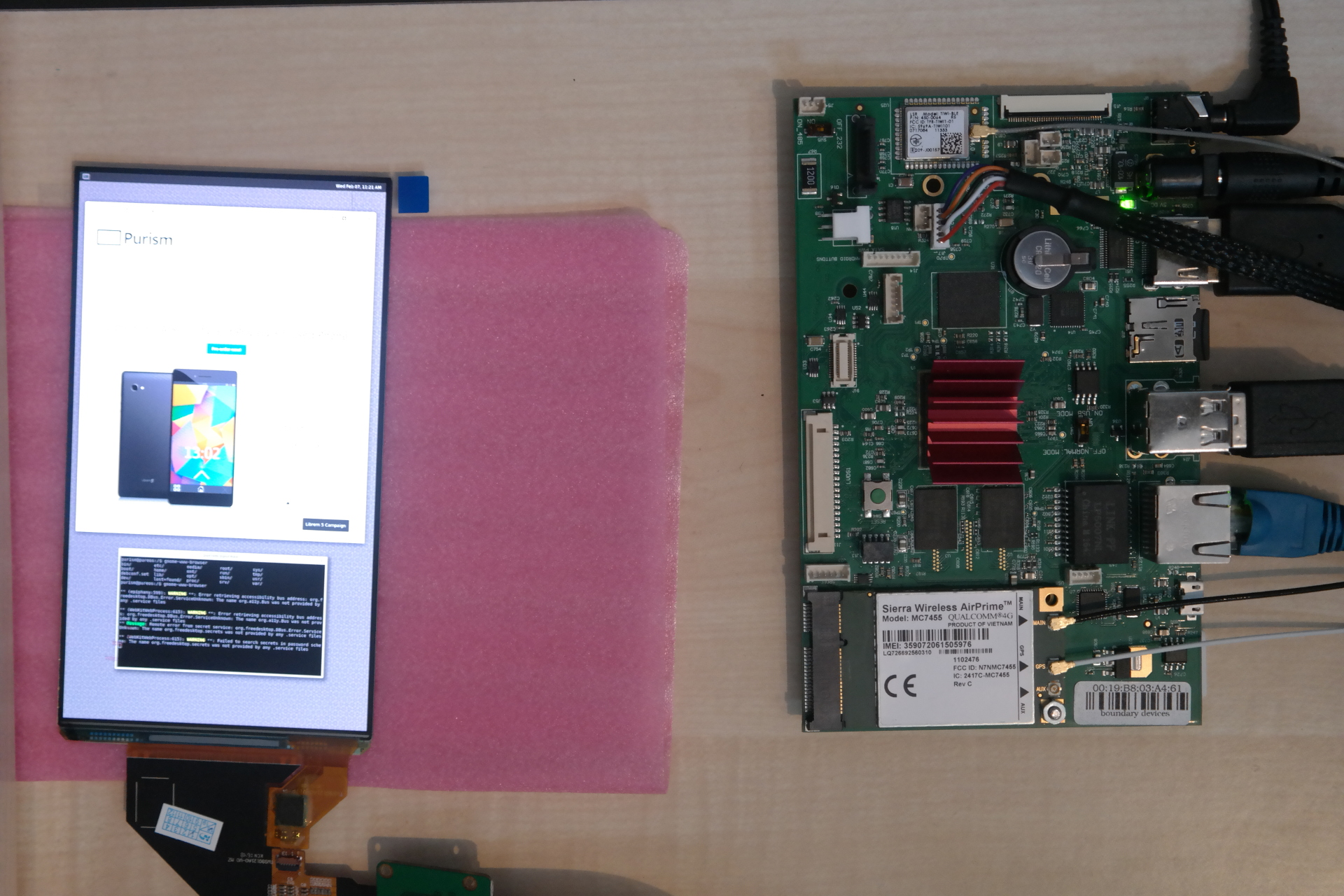

As I mentioned before, we have the i.MX 6 QuadPlus test hardware on hand, so here are some photos of our development board actually running something:

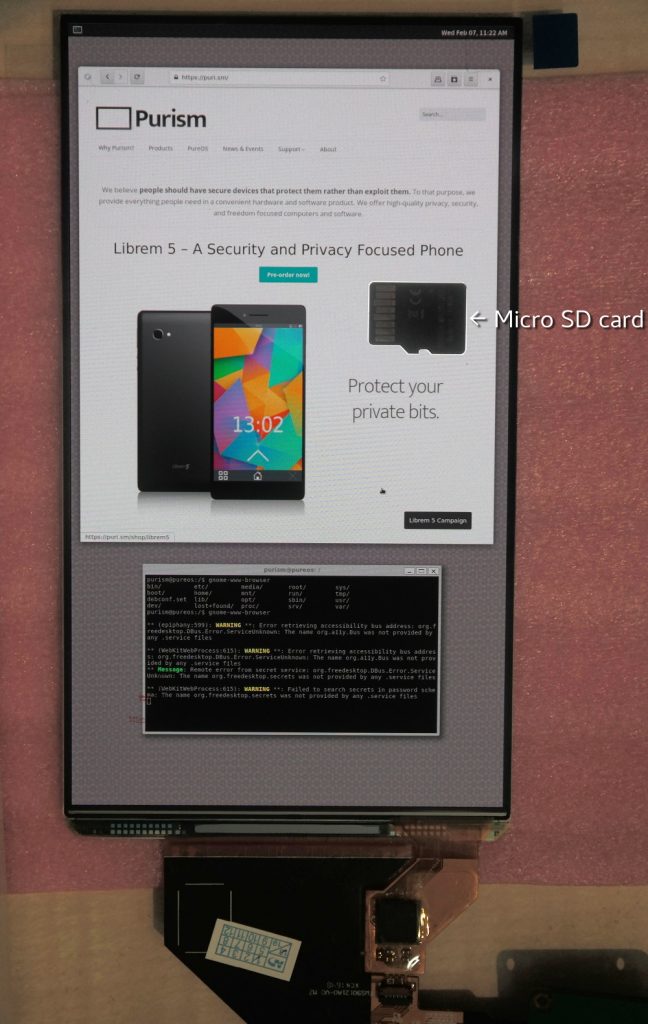

On the right, you can see the Nitrogen board with the modem card installed. On the left is our display running a browser displaying the Purism web-page and below it a terminal window in which I started the browser. To put the resolution of the display into perspective I put a Micro SD card on the display:

The terminal window is about as big as three Micro SD cards! This makes it very clear that a lot of work has to be put into making applications usable on a high resolution screen and to make them finger friendly since the only input system we have is the touch screen. In the next picture I put an Euro coin on the screen and switched back to text console:

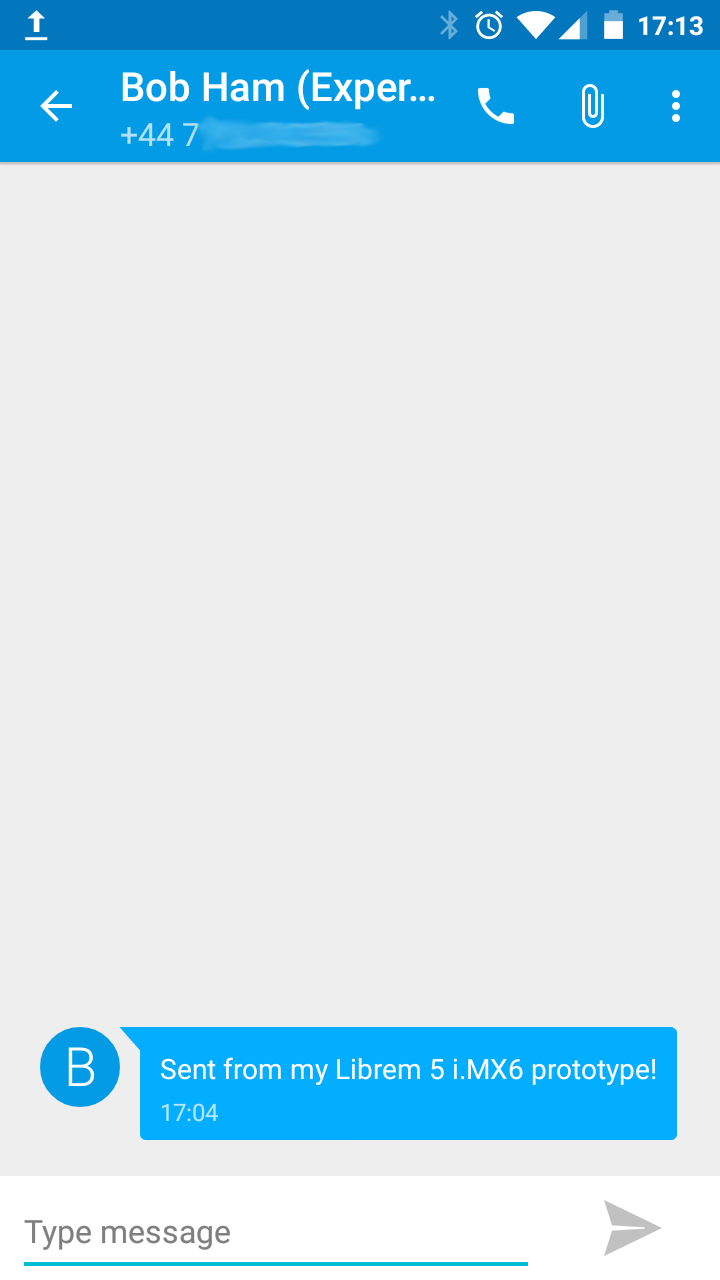

Concerning the software, we are working on getting the basic framework to work with the hardware we have at hand. One essential piece is the middleware that handles the mobile modem that deals with making phone calls and sending and receiving SMS text messages. For this we want to bring up oFono since it is also used by KDE Plasma mobile. We have a first success to share:

This is the first SMS sent through oFono from the iMX board and the attached modem to a regular mobile smartphone where the screenshot was taken. So we are on the right track here and have a solution that is starting to work that suits multiple possible systems, like Plasma mobile or a future GNOME/GTK+ based mobile environment.

The SMS was sent with a python script using the native oFono DBus API. First the kernel drivers for the modem had to be enabled followed by running ofonod which autodetects the modem. Next the modem must be enabled and brought online (online-modem). Once this was done sending an SMS was as simple as:

purism@pureos:~/ofono/test$ sudo ./send-sms 07XXXXXXXXX "Sent from my Librem 5 i.MX6 dev board!"

The script itself is very simple and instructive. Simulating the reception of a text message can also be done, with a command such as this one:

purism@pureos:~/ofono/test$ sudo ./receive-smsb 'Sent to my Librem 5 i.MX6 dev board!' LocalSentTime = 2018-02-07T10:26:19+0000 SentTime = 2018-02-07T10:26:19+0000 Sender = +447XXXXXXXXX

The evolution of mobile hardware manufacturing

We are building a phone, so hardware is an important part of the process. In our last blog post we talked a bit about researching hardware manufacturing partners. Since we are not building yet-another Qualcomm SOC based phone, but starting from scratch, we are working to narrow down all the design choices and fabrication partners in the coming months. This additional research phase has everything to do with how the mobile phone hardware market has evolved in the past years and I want to share how this all works with you.

In the early days of smartphones, a common case was that the main CPU was separated from the cellular baseband modem and that the cellular modem would run its own firmware when implementing all of the necessary protocols that operate the radio interface—at first it was GSM, then UMTS (3G) and finally LTE (4G). These protocols and the handling of the radio interface have become so complex that the necessary computational power for handling this as well as the firmware sizes have grown over time. Current 3G/4G modems include a firmware of 60 or more megabytes are becoming more common. It did not take long before storing this firmware became an issue as well as at run time since this requires significant increases of RAM usage.

Smartphones usually have a second CPU core for the main operating system which also runs the phone applications and interacts with the users. This means that your device must have two RAM systems as well, one for the baseband and one for the host CPU. This also means you need two storages for firmware, one for the host CPU and one for the baseband. As you may imagine, getting all of these components working together in a form factor small enough to fit into someone’s hand takes a lot of development and manufacturing resources.

The advent of cheap smartphones

There is extreme pressure about the cost of smartphones. In today’s commodity market, we see simple smartphones starting at prices less than $100 USD.

The introduction of combined chips, with radio baseband plus host CPU on one silicon die inside one chip, massively reduced costs. This allows the host CPU and baseband to share RAM and storage. Since the radio can be made in the same silicon process as the host CPU, and both can be placed in a single chip package, we see substantial cost reduction in the semiconductor manufacturing as well as the cost of manufacturing the device. This saves you from having to use a second large chip for the radio itself, an extra flash chip for its firmware, and possibly an extra RAM chip for its operation. This does not only reduce the Bill of Materials (BOM), but also PCB space, and it enables the creation of even smaller and thinner devices. Today we see many big companies offer these types of combined chipsets—such as Qualcomm, Broadcom, and Mediatek to name a few.

These chips caused a big shift in the mobile baseband modem market. Formerly it was common to find discrete baseband modems on the market that were applicable for mobile battery powered handsets like the one we are developing. But since the rise of the combined chipsets, the need for separated modems has dropped to a level that does not justify their development as much. You can still find modem modules and cards but these modules are usually targeted for M2M (machine to machine) communication with only limited data rates and most of them do not have audio/voice functions. They usually come in pretty large cards, such as the miniPCIe or M.2. For us this means that our choice of separated baseband modems suitable for a phone is narrowed.

What this means for OEM, ODM or Build it Yourself

All of this consolidation has an impact on hardware manufacturers and our choices. Pretty much all current smartphone designs by OEM/ODM manufacturers are based on the combined chipset types; this is all they know and it is where they have expertise. Almost no one is making phones with separated basebands anymore, and the ones who do are not OEMs nor ODMs. The options are further limited by our requirement not to include any proprietary firmware on our host CPU (which we wrote about before): most fabricators are unfamiliar with i.MX 6 or i.MX 8 and do not want to risk a development based on it, which narrows our hardware design and manufacturing partners to a much smaller list.

However, we have some promising partners that we will continue to evaluate, and we are confident that we are going to be able to design and manufacture the Librem 5 as we originally specified. We just wanted to share with you why making this particular hardware is so challenging and why our team is the best one to execute on this design. To continue to discuss with some of the manufacturers and providers, Purism will visit Embedded World, one of the world’s largest embedded electronics trade shows, in Nürnberg (Germany) in the beginning of March. And, as usual, we will continue to keep you updated on our progress!

Good news with our existing evaluation boards

We have been patiently waiting for the i.MX 8M to become available, all according to the forecast timeline from NXP. In the meantime, we have started developing software using the i.MX 6 QuadPlus board from Boundary Devices, specifically the NITROGEN6_MAX (Nit6Qp_MAX) since it is the closest we get to production devices before NXP releases the i.MX 8M. We have a Debian Testing based image running as a testbed on these boards while the PureOS team is preparing to build PureOS for ARM and ARM64 in special.

On these evaluation boards we have all the interfaces that we need for software development:

- Wi-Fi

- Video input and output

- USB for input devices

- Serial console and a miniPCIe socket with SIM card connected for attaching a mobile modem

- At the moment, we are using a Sierra Wireless MC7455 LTE miniPCIe modem card for development, which uses a Qualcomm MDM9230 baseband modem chip. This card is basically a USB device in a mPCIe form factor, i.e. we do not actually use the PCIe interface.

- An extremely nice display to our kits using an HDMI-to-MIPI adapter board. The display is a 5.5″ AMOLED display with full-HD resolution with the native orientation as portrait mode.

This hardware setup allows us to start a lot of the software development work now to ensure our development continues in parallel until we have the i.MX 8M based hardware in hand.

Next on our to-do list: phone calls!

Recent Posts

Related Content

- Google Mishandling School Children’s Data

- Ethics over Exploits – Use PureOS over Android/iOS

- Hidden Operating Systems in Chips vs. Secure, Auditable OSes: A Cybersecurity Comparison

- Apple Moves iPhone Production to India—Purism Has Been Leading the Way for Years

- What Is PureOS? A Beginner’s Guide for iOS, Android, and Windows Users