Manufacturing the Liberty Phone in the United States of America

Todd Weaver

PGP Fingerprint: B8CA ACEA D949 30F1 23C4 642C 23CF 2E3D 2545 14F7

Latest posts by Todd Weaver (see all)

- Hardware Encrypted COMSEC Bundle by Purism - April 29, 2024

- Purism Differentiator Series, Part 14: Surveillance Capitalism - April 23, 2024

- Purism Differentiator Series, Part 13: Modularity & Right to Repair - April 23, 2024

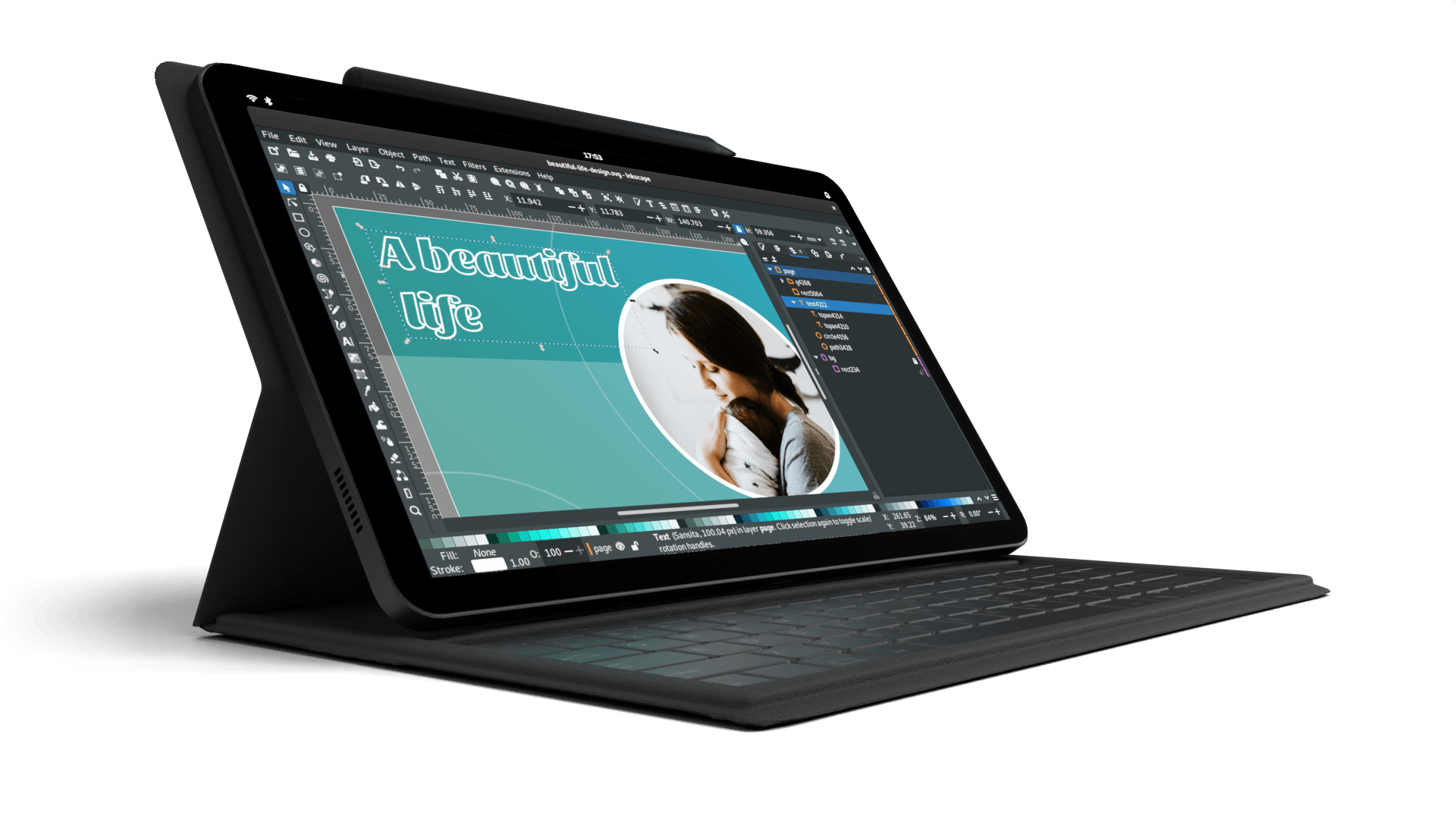

Making a phone that avoids Big-Tech spying is one thing (yep, we did that). Making a convergent operating system that is not Android nor iOS is another (yep, we did that too). But manufacturing that phone in the USA is a feat that few thought possible (yep, did that just now). Not only have we proved it’s possible… it’s shipping.

The Liberty Phone

One of the many industry-changing goals Purism had set—and now accomplished—was to manufacture our Librem 5 phone in the USA, including doing all electronics manufacturing in our facility (note: we have already been doing this for a few years with the Librem Key—Made in the USA). The Liberty Phone is a revolutionary phone with immense differentiators compared with the rest of the mobile phone industry. Making the most secure phone demands being able to have full verification of all steps from releasing schematics, using Made in USA electronics, releasing all source code, isolating hardware components, and running an Operating System that is under the full control of the customer—that is not cryptographically forced into Big-Tech’s oppressive and exploitative control—The Liberty Phone is all of those things.

One of the many industry-changing goals Purism had set—and now accomplished—was to manufacture our Librem 5 phone in the USA, including doing all electronics manufacturing in our facility (note: we have already been doing this for a few years with the Librem Key—Made in the USA). The Liberty Phone is a revolutionary phone with immense differentiators compared with the rest of the mobile phone industry. Making the most secure phone demands being able to have full verification of all steps from releasing schematics, using Made in USA electronics, releasing all source code, isolating hardware components, and running an Operating System that is under the full control of the customer—that is not cryptographically forced into Big-Tech’s oppressive and exploitative control—The Liberty Phone is all of those things.

Manufacturing the Liberty Phone

Parts

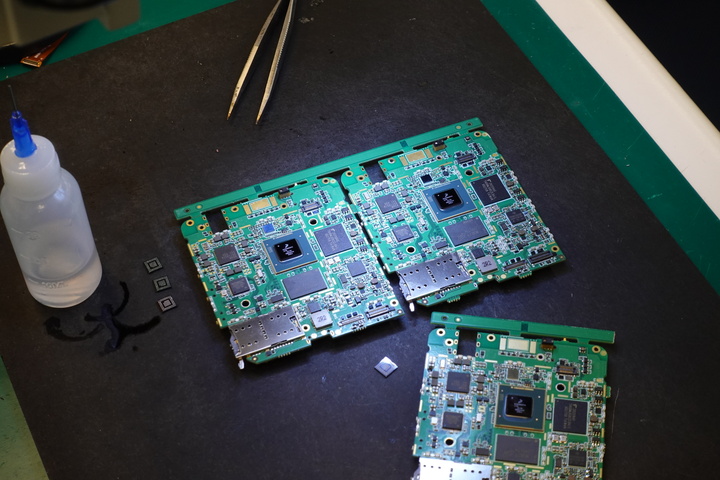

As an Electronics Engineer (EE) once told me “hardware is a compile once language”, while this is a slight oversimplification since you can repair hardware (as explained below), his point is not lost: once produced, hardware is painfully expensive to change. Preparing, procuring, planning, and triple-checking parts is essential to making sure you are able to produce hardware that works as designed.

It was already a challenge to produce a secure mobile phone that has a fairly complex board with over 140 unique and over 1,000 total parts—and that was before the largest parts shortage scare the industry has ever seen. Procuring the exact right parts is a line-by-line, part-by-part, package-by-package, reel-by-reel process that is saved only for the most patient and meticulous.

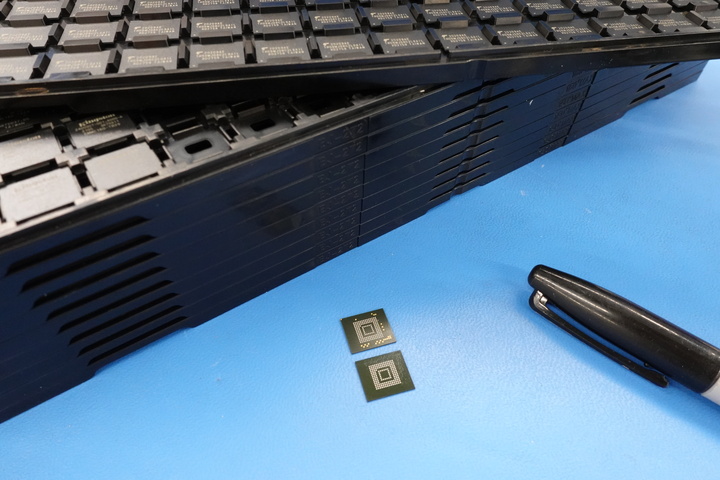

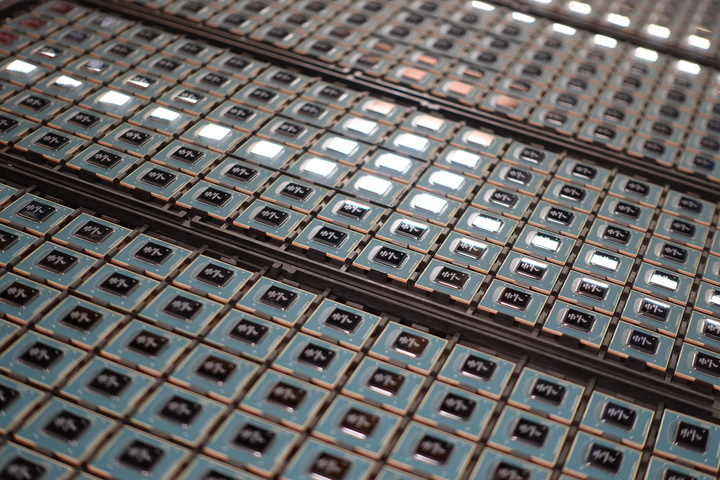

Fun side story, one brand of 32GB eMMC has test pins on the underside that confuses the optical scanner for SMT parts placement, while another brand does not have the test pins. Since there is no easy way to mask the optical scanner of those test pins, a black permanent marker is a quick fix to blot them out so as not to confuse the scanner.

Another part of the parts story is replacing the End of Life (EOL) 3GB RAM for (the more expensive) 4GB RAM (that still represents itself as the 3GB max available from the CPU), these parts alternatives are entirely due to the Ball and Supply Chain shortages. Procuring enough safety stock to manufacture for the next year is critically important with the current uncertainties in the supply chain.

Once you believe to have all the parts triple-checked against your Bill Of Materials (BOM), the process of kitting can begin.

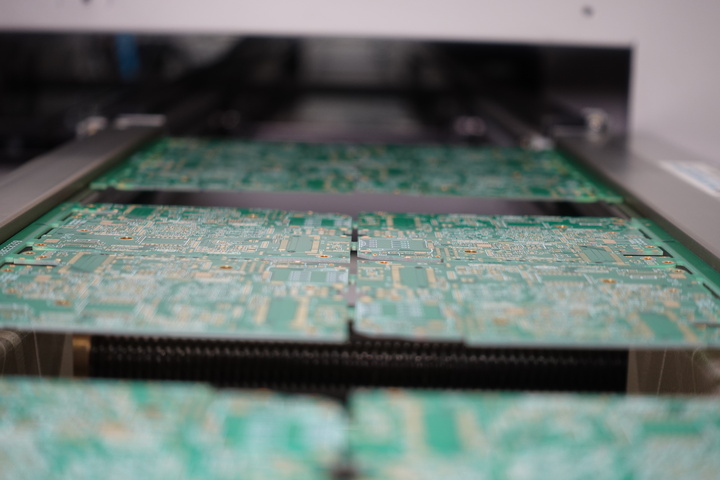

Kitting

This probably varies a bit from outsourced CM to in-house manufacturing, in our in-house case we scan and load parts into feeders or trays for the (GNU/Linux based) SMT machines to import easily into its magazines. This kitting process is yet-another test against the BOM where upon entering into the database the parts get matched to orientation (pin 1) for the SMT head to place and inspect properly across the entire top (and then bottom) of the Printed Circuit Board (PCB).

PCB

According to every single line operator I have met there has never been a PCB they have liked. You can hear the groan from across the room when they discover one smaller-than-desired solder pad. Fixing that means adjusting the pad itself or adjusting solder quantity to make sure the part gets proper connection without floating off the pad and wreaking havoc on neighboring parts.

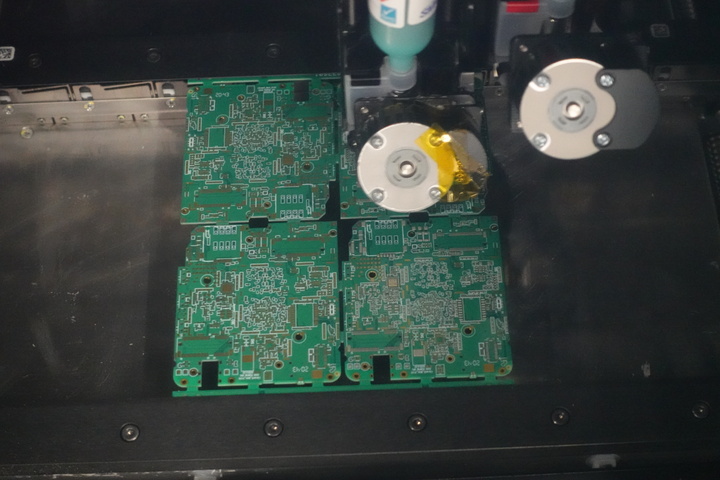

In our case we use rapid development SMT which utilizes solder paste (think inkjet printer) to lay the paste onto the board before inspection.

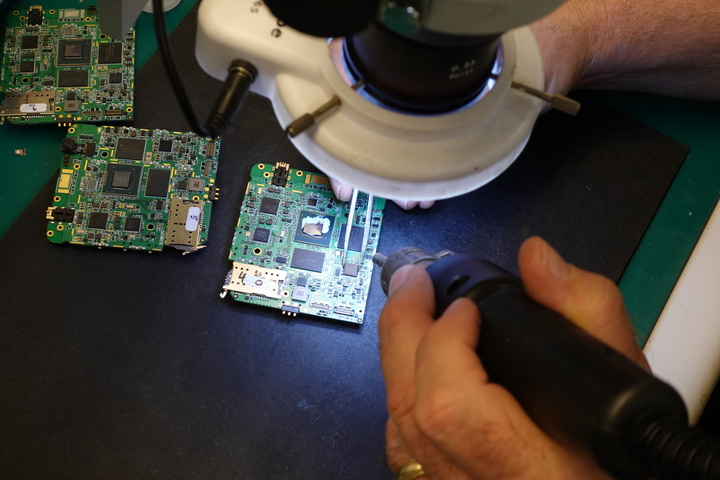

Inspection

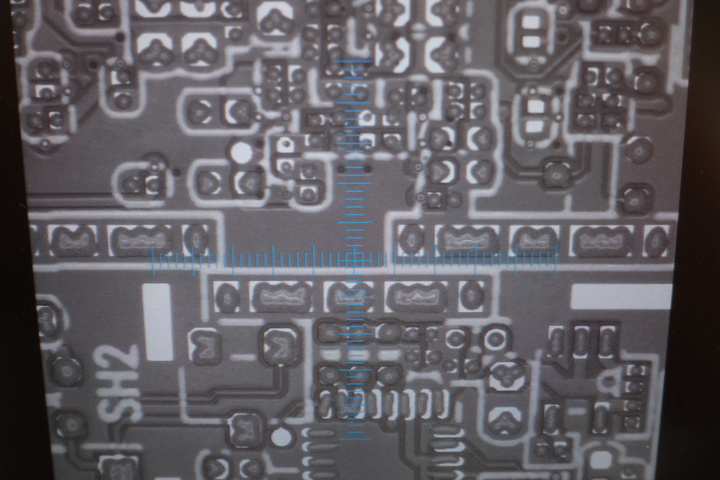

Initially inspection is a combination of machine inspection and manual inspection. As volume increases, inspection is less manual inspection and more fully automated. The first panels are inspected under a microscope pad-by-pad on top and bottom of the board, this helps ensure all subsequent processes are done with minimal error.

Surface Mount Technology

SMT is basically giant parts printing and the wow-factor of what these machines can do is short-lived, because having expert line operators makes it all seem pretty routine. The process from solder paste, to pick-and-place, to vapor phase (this is the process we utilize) means that most all of the excitement waits until when the boards are actually brought up after thorough inspection.

Board Inspection

Inspecting the first few panels and board manually (which is done before setting up Automated Optical Inspection (AOI)) helps confirm parts are on pads and there are no “tombstones” or “billboards” where parts lift off a pad or rotate on a pad. When these issues arise, it is important to hand fix them, as well as see if it was a solder issue (too much on one pad or too little on another) that can allow these parts to float in solder soup.

A common misconception around SMT and PCBA production is that a “failed” board is tossed/recycled (like printer paper where when you make a mistake, just print another); this is the polar opposite of what actually occurs. While the desire is to iterate and improve to have no SMT errors, the earliest of boards off a line have a lot of hand inspection and correction. Another misconception is that a machine placed part is in some way superior to the same connected part placed by hand. It’s not. It’s faster and more efficient, but hand (re)placement is equally stable. Electronics off a line are hand repaired more often than people understand. This only increases cost (labor and time), it doesn’t reduce reliability. After you inspect boards and repair obvious issues, it’s time to bring up the board.

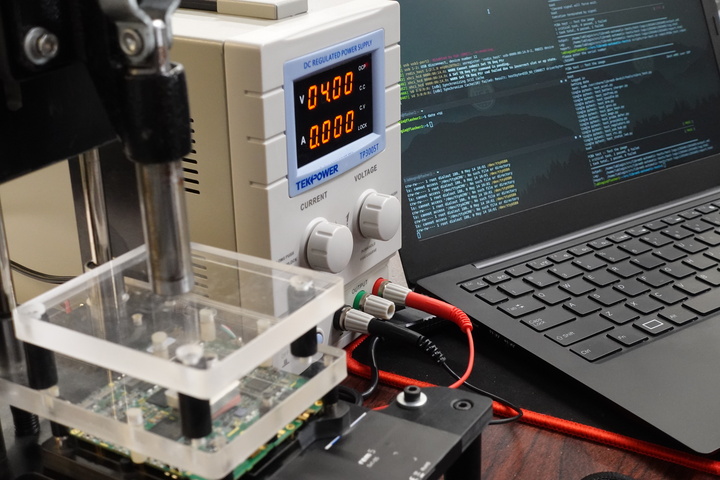

Board Bring Up

Bringing up a board for the first time is exciting and nerve-racking: first put a fresh-out-of-the-oven PCBA into a test jig, make sure the pogo pins align and connect, current limit the power supply, and then take a deep breath of clean air before it may fill with blue smoke. The common debug cycles apply to board bring-up, it is a development environment, so produce only a few boards, and systematically go through every part and trace to make sure every single component acts as desired.

Power on, if current is good proceed; in the case of the NXP CPU used in the Librem 5 booting over Serial Download Protocol (SDP) supports automated scripting to probe (bring-up) each part across the schematics to see how far you get before a failure (also referred to as issues to make them sound less severe).

Addressing Issues

Let’s say hypothetically that a Texas-based Instrument and parts maker has a part, let’s say that part is something like a TPS65892 (revision AB), and like all parts that Electronics Engineers (EEs) select, needs to be kitted exactly to part number (TPS65892) and package (NFBGA 96). Normally parts vary by part number (I am pretty sure it’s why they’re called part numbers), but in rare instances (I can think of only one) that part is a completely different part if it is appended by what you normally would read as a revision number: TPS65892BB. In this example these are pin-matching parts that do completely different things and where all things work fine with the exception of charging the battery and providing USB connectivity. After a number of hours tracing schematics to board read values, this hunting manifested itself into a data sheet comparison where we learned these are unrelated parts. <insert parts procurement scramble />. After getting the correct part, the incorrect part is desoldered and correct part is soldered on to test. In this case all things test positive and we now are proud owners of a giant quantity of (incorrect) TPS65892BB chips that we get to worry about later.

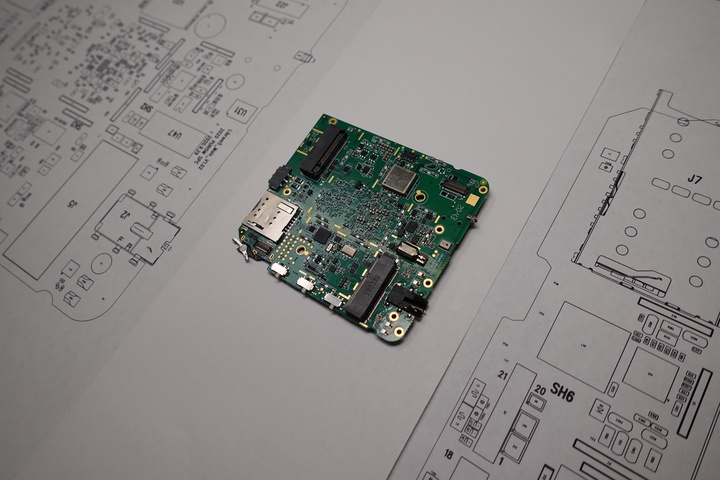

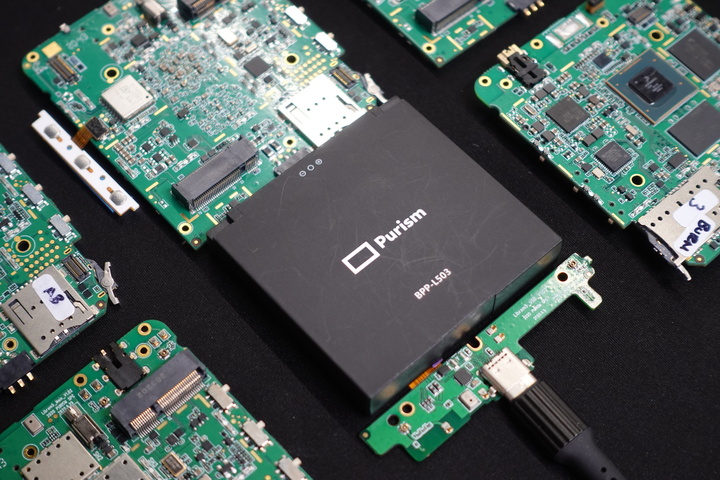

Upon the first panel (in our case we have qty 4 boards per panel) passing through all tests, it’s time to move onto a quick assembly test of the first full Liberty Phone.

First Full Liberty Phone

This image speaks for itself. Time for the line to spin up.

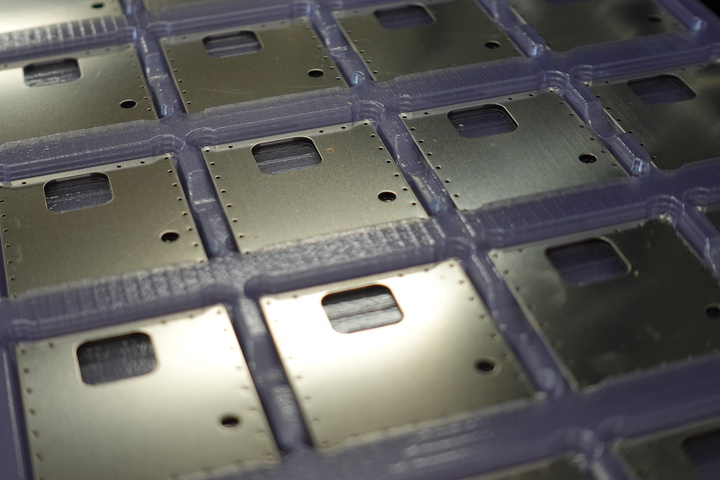

Spin Up

Giving the green-light for a mass production feels extremely satisfying (due entirely to the expert staff Purism has that puts the mind at ease that mass production will yield functioning product). Machines begin to whir in a repetitive sounding motion that is remarkably comforting, only interrupted upon a reel running out alarm that creates a fluid and natural flow for the line operators to load more parts on. Parts are placed, panels are separated, through hole parts are added, and now we enter per-PCBA testing.

PCBA Testing

Using the same tools during board bring up, the process is streamlined: note serial number label, provide power, script test all components work, log the results, flag errors for rework (rework and repeat), rack successes for assembly.

Assembly

Almost everywhere assembly is done at separate facilities from manufacturing (this is typically called Contract Manufacturing (CM)), but at Purism we do it all from within our same facility, so we don’t have to package and ship, we just wheel the cart to the assembly team. Assembly initially is done by a manager doing all the steps, timing them, and iterating and improving. We not only assign stations to the tasks, we also happen to rotate staff stations to have full redundancy of all stations. Assembly of the Liberty Phone is a meticulous process that includes a very specific order and tight tolerances. After a successful assembly the Liberty Phone enters testing.

Testing

Testing begins by flashing the PureOS testing image, conducting an interactive phone test to confirm all peripherals work (or get reworked, sometimes via re-assembly, sometimes by going back to PCBA testing (and iterating to improve the tests there)), upon successful testing it enters final quality control.

Quality Control

The process of physical inspection and physical interaction with the device to make sure all things work properly, volume rocker buttons, power button, WiFi, sound, headphones, speaker, hardware kill switches, modem, SIM card, PGP smart card reader, battery, battery charging, cables, microphones, cameras, proximity sensor, haptic (vibrator) motor, touch, multi-touch, display, flashlight (torch), etc. are all manually tested before reflashing the customer-facing PureOS image for shipping.

Shipping

The shipping team assigns the serial number to the customer order, makes sure the box is full of all contents and the packing slip matches the goods, box, label, rack for carrier pick-up. There is a high degree of satisfaction of seeing racks of product for pickup and delivery to customers who will be able to own a Liberty Phone that has Made in USA Electronics.

Conclusion

Making the Liberty Phone is the latest revolutionary advancement Purism has delivered on, proving it not only possible to make a phone that is secure, avoids Big-Tech, never spies, never tracks, is not monopolistic, has all the source code released, and allows the customer to actually own it, but also is manufactured in the United States of America. Support Purism and our efforts by ordering all your computing products from Purism including the Liberty Phone.

Purism Products and Availability Chart

| Model | Status | Lead Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Librem Key (Made in USA) | In Stock ($59+) | 10 business days | |

| Librem 5 | In Stock ($699+) 3GB/32GB | 10 business days | |

| Librem 5 COMSEC Bundle | In Stock ($1299+) Qty 2; 3GB/32GB | 10 business days | |

| Liberty Phone (Made in USA Electronics) | In Stock ($1,999+) 4GB/128GB | 10 business days | |

| Librem 5 + SIMple (3 GB Data) | In Stock ($99/mo) | 10 business days | |

| Librem 5 + SIMple Plus (5 GB Data) | In Stock ($129/mo) | 10 business days | |

| Librem 5 + AweSIM (Unlimited Data) | In Stock ($169/mo) | 10 business days | |

| Librem 11 | In Stock ($999+) 8GB/1TB | 10 business days | |

| Librem 14 | In Stock ($1,370+) | 10 business days | |

| Librem Mini | July 2024 ($799+) | 15 business days | |

| Librem Server | In Stock ($2,999+) | 45 business days | |

| MiMi | Crowdfunding ($500+) | tbd |

Recent Posts

- Avoiding a Monoculture with Secure Diverse Technology

- Private Cellular Networking and Secure Client Devices

- Abside and Purism Partner to Deliver Secure Mobile Solution for U.S. Government and NATO Countries

- Purpose-Built Smartphones for Government vs. Commercial Off-The-Shelf Devices

- Purism Announcing MiMi Robot Crowdfunding Campaign

Related Content

- Abside and Purism Partner to Deliver Secure Mobile Solution for U.S. Government and NATO Countries

- Your Phone is Giving Away More Than You Ever Bargained For

- From the Hackdesk: Librem 16

- Purism Announces First Public Offering on StartEngine

- Purism Liberty Phone to be Featured in Orpheum Films Collaboration